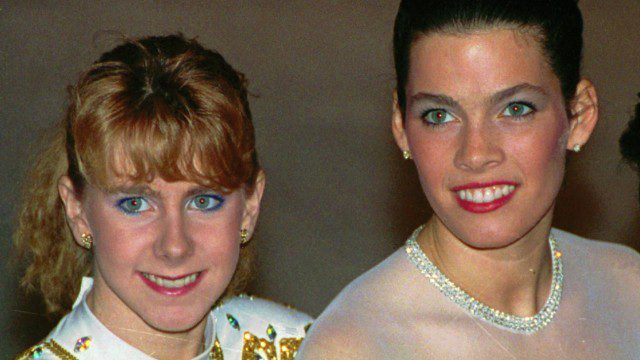

With the Winter Olympics and Paralympics now over, it comes as no surprise that one of the pejoratively greater stories was the judging controversy of the figure skating competition, and how it reinforced long-standing stereotypes. The overcooked scores for the skaters on home ice had many puzzled, particularly by the victory of a graceless Russian teenager in the hotly-contested ladies competition. Those in the know questioned what was going on behind the scenes. The speculation elevated when cameras actually did catch a telling glimpse backstage as one of the judges (and wife to the Director of the Russian Skating Federation), hugged and congratulated the winner, Adelina Sotnikova, after Yu Na Kim of South Korea had received her second place marks. (For the record, I thought Carolina Kostner of Italy should have won gold, not Kim, but that is a discussion for another time). Without the increased presence of cameras, we never would have discovered this breach, and it reminded me of how the sport first attracted a level of attention that necessitated this presence invading every nook and cranny of figure skating venues. To “celebrate” the 20th anniversary of the biggest story in figure skating history, we got another controversial competition-between NBC’s documentary “Nancy and Tonya,” and ESPN’s “The Price of Gold,” that aired a few weeks earlier; two films about the legendary Tonya Harding/Nancy Kerrigan soap opera that gave birth to a problem child unlike any known in sports history.

These films plunged me back into an era when mullets were still popular and Miley Cyrus’ dad had a hit record, and a time when everyone had gone crazy for something I loved: the broadcast of the Ladies Figure Skating competition at the 1994 Winter Olympics in Lillehammer, Norway. This competition drew bigger ratings than any other event in Olympic history, and more than all but 2 Superbowls in the history of televised sports, period. The story of the attack took complete control over the news and helped figure skating spiral into parts of American society and culture I had always thought immune to it. To explain how intense the interest was, respected reporters like Tom Brokaw (as you can see in the films) had to begin broadcasts from the Capitol, or Moscow, or a building destroyed by a natural disaster, with a rundown of the latest details in the Kerrigan/Harding affair. If I was old enough to go to a sports bar at the time I could have successfully requested the bartender change the channel to the figure skating competition, if they didn’t already have it on.

“The Price of Gold” by Nanette Burstein, part of ESPN’s commemorative documentary series “30 for 30,” covers this time with sincerity, intelligence, and journalistic depth. “Nancy and Tonya” is the project of broadcast sports commentator/former tennis player Mary Carillo, and aired in the prime slot preceding the closing ceremonies of the #sochifail Winter Olympics of 2014. Though it opts for a less investigative approach, “Nancy and Tonya” has the plum of featuring Nancy Kerrigan, who hasn’t spoken about any of this for years. But “The Price of Gold” trumps that queen with the more entertaining ensemble of impressive finds among its interview subjects, all spectacularly prepared with money quotes regarding these skaters and this story. These two films timed their visibility to capitalize on the first Winter Olympic games to have such a huge media interest (for even more unfortunate reasons) since Lillehammer. I was happy as a clam for this chance to revisit how the world fixated on these wild trials and tribulations. No man, woman or child could resist rubbernecking at what erupted when these two disparate sides of the same coin crashed into each other in a real docudramedy of epically insane proportions. And just like the skaters they talk about, one film is a resounding victor of the showdown.

In comparing the movies to each other, some telling, obvious similarities and omissions emerge readily. Burstein and Carillo take enjoyable pot-shots at the stupidity of the criminals who carried out the attack, and their interview subjects clearly have the most fun talking about this. One of the more heartening similarities is that neither film attempts to take away Tonya’s historic achievement of completing the triple axel in competition (4 times) in 1991, a monumental accomplishment that only 7 women in the history of the sport can lay claim to. Boston Globe reporter John Powers says in “Gold” that “the feeling from within the sport, the officials, was ‘God, look who’s our champion?’ There was no question that Tonya Harding was not the image that figure skating wanted. But when you do a triple axel, it’s pretty hard to take it away from her.” Though Mary Carillo’s “Nancy and Tonya” reiterates the vilification of Tonya that comes so easy to all of us, this one aspect of her life it gives complete, awed credit to. A glaring omission in both films however, is the lack of interviews with Tonya’s longtime coach Diane Rawlinson. Though we have old clips, we don’t see any comment from her past the 1994 Olympics, when the shit hit the figure skating fan and sprayed all over the world.

Before any shenanigans went down, these two women grew as skaters from the same athletic-minded foundation. Their lives off the ice however could not have been any more different and their presence on the ice reflected how factors like love, support and stability, or the lack thereof, can change things dramatically. Burstein and Carillo bank on the stark contrasts between Kerrigan and Harding to shape the angles their films take. Nancy was a great athlete with a sense of pragmatism bred by her blue-collar (but more stable) upbringing. As an added bonus, she had the looks and height to be more easily molded into the preferable “ice princess” that the skating world (fans, judges, advertisers and governing bodies of the sport) wants women to be, complete with free couture costumes by Vera Wang. She was built to play “the game” and abide the rules of ladylike conduct in figure skating. Tonya was destitute, determined, physically and emotionally abused, and possessed a strong rebellious streak. She had more muscle than glamour, untamed hair and yellow teeth, questionable taste in music (she “wanted to skate to ZZ-Top”) and costumes she made herself (from an early prototype of the Bedazzler?). She never did what she was told if it didn’t feel right to her, making her a difficult skater to coach and simultaneously more willing to take risks. With so little in her life under her control, she would not let anyone control her skating…or so she thought.

While “Nancy and Tony” spends more time trying to help us appreciate what a great gal Nancy is at the expense of a more fruitful purpose, “The Price of Gold” takes a bolder stance and speaks more deeply to how the issues of abuse, class and socially constructed femininity helped produce the events that changed figure skating forever. Each film, in turn, noticeably assumes the personalities of the skater it focuses on. “Nancy and Tonya” ends up playing it more traditional, (Nancy), while “The Price of Gold” takes a risk and dares to humanize its reviled star (Tonya). “Nancy and Tonya” never challenges the conventional wisdom, while “Gold” takes the hard road to find out what could have brought this bizarre tale to fruition. As Harding’s childhood friend Sandra Luckow says in “Gold,” the story was “so rich in its blacks and whites-nobody needed the gray.” Where Carillo’s film sticks to the blacks and whites, Burstein chooses instead to explore the gray to create fully realized people out of these polarized figures.

At best, “Nancy and Tonya” proves either that Kerrigan’s ability to connect with an audience has improved tremendously since she skated competitively, or that she genuinely has moved on and harbors no ill will towards Tonya. At worst, this was its only discernible goal. Shortly after her controversial loss in a tiebreak on the artistic mark (to the pitiable Oksana Baiul whose train wreck life after these Olympics could spawn a whole other movie), the press turned on her for some unfortunate comments caught by the new sea of open mics hanging around. Carillo’s is most determined to explain why Nancy lost her composure for a split second under great stress. What nobody told Carillo is that we already know why. It was Nancy’s reaction under stress that people criticized, so the film is doomed to fail just like Tonya was at the Olympics. The only other thing the film has to say is that Nancy was a better person than Tonya, the criminal who dug her own grave. To keep from letting the black and white bleed together, Carillo avoids including information that complicates her simplistic victim/villain dichotomy. Award-winning sports journalist and best-selling author Christine Brennan is the only person in the film to make any critical statement about Nancy, and it’s only a comment on her skating (that she may have failed to win gold, not because she didn’t deserve it, but because she lacked the ability to “relate to the audience” and judges with her skating).

While Nancy certainly had much to cope with, I don’t think she would trade any part of her life for that of the woman to whom she will be forever linked. Portland TV reporter Ann Schatz who followed the drama from the very beginning (and whom Carillo does not include in her film) contributes many valuable pieces to the great puzzle of Tonya Harding. In “Gold,” she lays down the most vital point to understanding her:

There was poverty in this young girl’s world that we need to understand, because it’s part of this story. She skated a lot of times without food in her stomach. She skated not really understanding if that next lesson was gonna come or not, because she didn’t know if she could pay for it. And she knew she was good at one thing. And that was skating. She knew she could hang her hat on that one thing. Where nobody could tease her, nobody could take anything away from her, nobody could mock her, nobody could make her feel less than.

Burstein’s whole film hinges on remembering how these things, coupled with constant abuse, affect human beings and their futures, while never failing to hold Tonya accountable for her actions. And it makes clear that despite her considerable accomplishments in the sport before the “whack heard ‘round the world,” figure skating associations, sponsors, and corporate America could indeed make her feel less than.

In the light of Burstein’s hard-hitting approach, Carillo’s Nancy-centric one frequently lacks the depth required to give us the whole story. When Brennan mentions that the FBI got involved with the investigation of the attack, Carillo’s film never bothers to mention how this came about. But it’s a fascinating turn in the plot. If you had watched “The Price of Gold” first, you would know that Schatz had received an anonymous handwritten letter implicating Tonya and her ex-husband Jeff Gilooly, and used it to garner an interview before surreptitiously sending it to the FBI. It was after her actions that the FBI investigated, which “Gold” weaves into their exploration of how this plot and its consequences came to be, and what they ultimately cost Harding. Carillo says in a voiceover that “a string of mediocre results” threatened Tonya’s chances of making the Olympic team in 1994. Yet she doesn’t mention in conjunction that Tonya’s volatile, abusive marriage consumed her life at this moment, because it contradicts the line she has taken: that Harding made a habit of lazily wasting her best opportunities for success. She also erases the fact that Nancy’s abysmal performance at the 1993 World Championships is what increased the tension of the 1994 Olympic trials, because it cost the U.S. team a third ladies spot, thickening the plot further. Carillo’s tendency to compress large amounts of information into short voiceovers doesn’t just leave tantalizing details unexplored. It acts as a not-so-subtle cover-up for redacting the story in ways that benefit Nancy’s image and enhance the already reviled image of Tonya.

Despite Carillo’s veneration of Nancy, it is Burstein’s film that succeeds in making Kerrigan a more likable person. “Gold” made Nancy a more interesting skater and helps us understand better how she recovered from the attack and what kind of competitor she was. It does get a little nervy by giving voice to sycophantic Nancy-supporters like Olympic silver medalist Paul Wylie and former Olympic Gold medalist/commentator Scott Hamilton (who contributes nothing of value to either film, other than proof that we needn’t pay attention to anything he has to say). But it also takes care to show Nancy as someone who did not see herself as a victim, because it stood in the way of her goal. She includes privately shot video that somehow eluded Carillo: one clip shows a beautiful moment with Nancy beaming uncontrollably as she steps on the ice for the first time since her attack, and others show more of Nancy’s drive and determination in physical therapy sessions, as interviews from other members of her camp, such as her sports therapist. I find it difficult to imagine why Carillo glossed over these details in another short voiceover and montage lasting about 20 seconds. Instead of any serious inquiry, Carillo makes time for pure nonsense like Hamilton’s exclamatory statements (“It’s awful, awful, evil, dark, bad, terrible stuff!”), and how he knew Nancy was strong because she glared at him for a misogynist joke he made at her expense when he first met her.

That the first image of Harding in “Nancy and Tonya” is her singing dreadfully at a karaoke bar performing the theme song from “Ice Castles,” is a pretty declarative statement that Carillo will be shooting ducks in a barrel throughout. [Side note: For those who don’t remember, “Ice Castles” is a campy melodrama from the late 70s about a young blond woman from humble origins with an innate gift for skating. The young woman loses her eyesight in a freak accident caused by her irrepressible need to skate, but eventually her boyfriend convinces her not to quit competing. Improbably, she learns to skate without being able to see where she’s going and performs flawlessly at her first event since going blind. Apparently blindness was what she needed to be perfect.] Though slightly inverted, it’s hard not to see the similarity: Nancy, the brunette, recovered from the assault and triumphed, but Tonya the blond let her problems hold her back, as if they were easily-discarded ephemera, that she was just too thoughtless to get rid of.

Part of the continuing fascination with Tonya Harding is how thoroughly she believes her own version of the story, even when it defies believability. Both films have an easy time disproving her most obvious lies. Carillo tries, terribly, to break Tonya’s resolve but never moves beyond the persistent self-delusions we have come to expect. It is often a mystery what is real and what is embroidered with fictional detail when Tonya speaks. Though Burstein has to battle Tonya’s front of compulsive fabrication, she wants to understand this woman. Perhaps this desire is what enabled her to break through and unearth some real, heartbreaking reactions that I don’t think any interviewer has ever truly found. In addition, Burstein’s use of video footage from close friends and local news sources coupled with close-ups that linger after Harding finishes speaking, provide more material to work with. Like skating itself, the more earnestly felt performance is the one that people remember, and Burstein succeeds in drawing this out of Tonya. We see a wider gamut of emotions here that makes it possible to tell when she is being genuine, evasive, or repeating a story whose validity she has convinced herself of by endless repetition. In particular, Harding’s reminiscence of winning nationals and landing her triple axel in ‘91, her memory of how the US Figure Skating Association treated her during her career, and about being banned from skating for life, show Tonya at her most honest, sincere and vulnerable. More importantly, they show how she acts when telling the truth. Burstein’s tactics help create a spectrum along which we can make finer distinctions about Harding’s behavior. Tonya was not giving Carillo anything close to what she revealed in “The Price of Gold” and this has everything to do with Carillo’s ineptitude as an interviewer and lack of focus as a filmmaker.

Burstein also hit the jackpot with subjects such as Mark Lund, the founder of “International Figure Skating” magazine. His poise and colorful delivery make clear that he has been waiting a loooong time for the moment to give this interview about the “Dynasty in real life” that transpired. Burstein scored the most impressive points of all by pulling in the eloquent and humorous Luckow, who knew Tonya since the first moment she skated at age three. She once, as a teenager, made her own film about Tonya’s troubled life (which both Burstein and Carillo pull clips from) and brought with her the fullest perspective of anyone interviewed for either film. Luckow is the most useful resource available in affirming the truth of some of Tonya’s most awful stories. With her insight, clips of a 6-year old Tonya telling a reporter that she hates to fall in practice “because you waste $200” suddenly seem all the more tragic. Carillo doesn’t question why a 6 year old child is concerned about financial woes, but Luckow tells us enough to explain how Tonya mother’s could make her aware of what her talent cost (such as the severe beating she witnessed in the bathroom at a competition). Prophetically, when she tried to tell Tonya’s coaches, Luckow was told to stay silent because the scandal and distraction of being removed from her parents would end Tonya’s skating career. We are left to ponder what might have happened in Tonya’s life had someone intervened and ended the cycle of violence early on.

But the reporter hungry for a scoop on you is an equally hard problem to shake. The influx around these women (literally around Tonya in the shopping mall ice rink she practiced in) irreparably altered news and media forever, and was itself a contrast in styles. While reporters wanted Nancy’s reactions (and wanted them to be volatile), they enveloped Tonya like hawks swarming some festering carrion. It was “reality TV before there was reality TV” as Brennan so aptly called it. It even drew in the “venerable New York Times” according to Connie Chung, who appears in both films to great effect. In “Gold” she definitively asserts that “everyone was there” and that “it was horrifying for most reporters” to stoop to this tabloid level, “but there they were.” Chung admits to Burstein, with no confliction, that CBS (who had the rights to the Olympic coverage at the time) knew the more they covered this scandal, the better their ratings would be. Though people often complain about the vampiric press sucking the lifeblood from the people in these meal-ticket stories, “they eat it up” Chung tells us in “Nancy and Tonya,” and they tuned in to this “terrible soap opera that had all the makings of Shakespeare.” From that point forward, nothing was out of bounds for a respectable journalist. That the films themselves are cobbled together like Frankenstein’s monster from this same overwrought media frenzy is no small coincidence.

As observed then and now, Tonya’s story reads like some twisted O. Henry story more than Shakespeare (sorry Connie). Tonya’s desperation to hang on to the gift that gave her self-worth, cost her the ability to ever use it again. Luckow suggests at the end of “The Price of Gold” that Tonya “created her own reality” as a survival mechanism, resulting in a tragically “an unexamined life.” ESPN chose to examine it, and created a great film. What “Nancy and Tonya” does best is prove why Burstein made the right choice to focus on Tonya. Carillo produced a feature-length commercial promoting Nancy Kerrigan, rather than a film investigating the most bizarre phenomenon in the sport’s history. Unlike the skating rivalry, where Nancy clearly ended on top in the end, Tonya’s film definitively trumps Kerrigan’s. By focusing the most on giving Nancy’s reputation a facelift, Mary Carillo effectively kneecaps her project more efficiently than the thugs who attacked Kerrigan. But by watching both films, you can piece together the story more fully than ever before. The characters may want to move on, but I will never forget those days and nights glued to every newspaper and TV for any new information on the drama and how it felt to have others to talk to about a sport I loved, even if for the worst of reasons. I doubt anyone who was alive then will ever forget it either, and in some way that’s a victory for Tonya more than for Nancy, however dubious the honor.

“The Price of Gold” – 10 stars out of 10

“Nancy and Tony” – 3 stars out of 10