“No tears, please. It’s a waste of good suffering.”

How does anyone take Clive Barker seriously? He is possessed of a child’s sense of horror, a “more is more” approach that is frankly embarrassing. Every scene of Hellraiser, Barker’s directorial debut, is so over the top that it’s hard to believe this film isn’t a parody. With its endless cavalcade of mind-numbing gore, viscera, and torture, this film paved the way for talentless gore merchants like Eli Roth and Rob Zombie, and the regrettable wave of juvenile, self-impressed torture porn that flooded movie theaters in the mid-2000s (think disposable dreck like Captivity and Turistas). Every piece of indefensible garbage meant only to confront the viewer’s senses – like Hostel or House of 1,000 Corpses or the insipid Human Centipede trilogy – can trace their lineage back here. In the 1980s, Stephen King called Barker the future of horror, and as much as I love King, I’ve never been happier that he was wrong. If someone says that they like Hellraiser, it’s akin to them saying they like Friday the 13th. Both are wretched films, but they’re old and have somehow attained classic status.

What should be a shocking, intriguing beginning is laughable today. We meet Frank Cotton (Sean Chapman) taking possession of the franchise’s famous puzzle box. Credit where it’s due: the puzzle box is a clever design, and a good use of practical effects. It’s one of the more effective parts of the film, and brings to mind the titular machine from Cronos. Unfortunately for Frank, the contents of the box are less pleasing: when he opens it, chains and hooks manifest themselves and pierce his skin, ripping him apart. Later, we see the room covered in parts of Frank. If this sounds like the kind of over-the-top grotesquerie one might see in a local haunted house, that’s because it very much is.

As much as I didn’t care for the opening, Hellraiser immediately sacrifices its most interesting character and instead focuses on Frank’s terminally boring brother, Larry (Andrew Robinson). He’s moving into the family home with his combative, condescending wife, Julia (Clare Higgins, pancaked in so much makeup that she looks waxen and ghoulish), and his daughter, Kirsty (Ashley Laurence, giving the film’s best performance by a mile). Robinson plays Larry as if he’s meeting a dare to make his character as lifeless as possible, and Higgins plays Julia as a shrewish nag, like Adrienne Barbeau’s character in Creepshow, only played straight. No one in this film is likable, which would be borderline forgivable if this were a slasher film. But Hellraiser aims for high Gothic art. It lands somewhere near silliness.

Larry’s blood is spilled in the new house, which, when spilled on the floor of the room where Frank died, brings Frank back to life as a shambling, bloody wretch. This is an interesting hook to hang a story on – no pun intended – because it sounds like it could be something right out of Lovecraft. Done right, Hellraiser could be a ghoulish look at the specter of grief and loss that can seep into a family. But, Hellraiser was directed by Clive Barker.

Frank’s resurrection is the film’s best sequence (maybe the only good one), and it’s here that Hellraiser comes close to what it wants to be. Accompanied by Christopher Young’s dark, bombastic score, the sight of Frank’s skeleton reconstituting itself is a bloody marvel, a triumph of practical effects worthy of mention alongside David Cronenberg or The Thing. It must have been expensive, though, because we actually see just enough of Frank (played in monster form by Oliver Smith) – or maybe it’s the one instance of Barker fighting his craving for more-more-more.

Hellraiser would work better as a three-hour-movie, or as the sequel to a film in which we get to know Frank. We meet him five minutes before his gruesome death, so he doesn’t impart any fright as a monster, nor does the film convince us of the connection between him and Julia, supposedly formed over the course of one passionate night before Julia’s marriage to Larry. I have a feeling this doesn’t hold water because Frank’s seduction of Julia looks more like rape, and because Frank is written as a rakish Han Solo type, but Chapman plays him as an entitled jerk. And because Julia is such a caricature of a harpy, we get no sense of her mental or moral decline when she agrees to kill people so Frank can use their blood to come back to life.

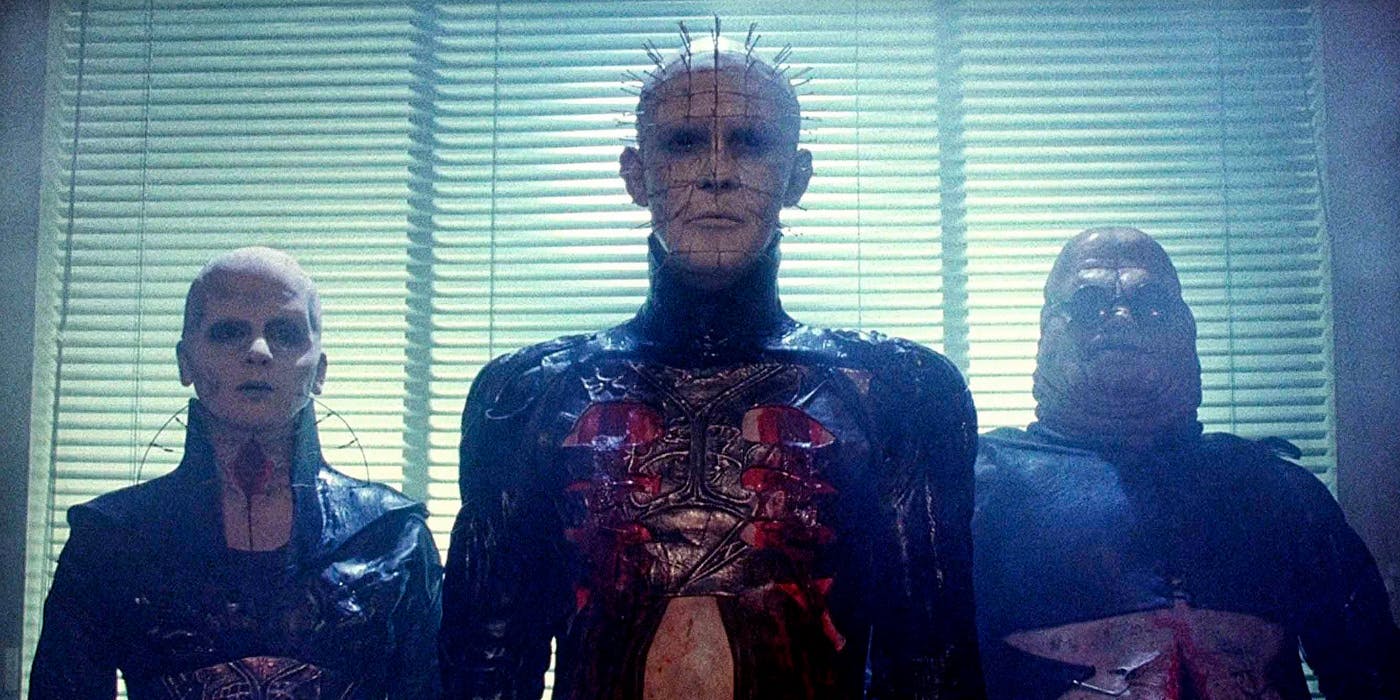

Everything about the iconography of Hellraiser – the poster, the imagery – revolves around the Cenobites, its cabal of hedonistic demons. But the film really wants us to buy into the Frank/Julia plot, to the point where we don’t even see the Cenobites until well over an hour into a 93-minute movie. Which is just as well, because the Cenobites are ridiculous from just about every viewpoint. They’re somewhat inventive as visual creations, but that’s about the last good thing I’ll have to say about them. Some of the names (like Chatterer) are fine, while others (Pinhead, Butterball) are just stupid. Then there’s the female cenobite, who has the terrifying name of…um, Female Cenobite. Pinhead is the franchise’s most iconic villain, and it’s evident why from an aesthetic viewpoint. But it doesn’t make sense past that, because the actor playing him, Doug Bradley, is awful in the role. (To be fair, almost everyone in Hellraiser is awful.) Bradley’s voice is not intimidating, nor is his physique, and his flat delivery makes lines that are scary on paper fall completely flat.

The most damning thing about Barker’s film is that it doesn’t even have the courage of its own convictions. “There’s such a fine line between pain and pleasure,” Pinhead says, but the film fails to explore or explicate this is any way. Barker envisioned the Cenobites as interdimensional beings who have evolved to the point that they can’t differentiate between pain and pleasure; he wanted to make a horror film about BDSM, but here focuses only on the gruesome pain. Yes, some peoples’ sexual experiences are amplified by inflicting or receiving pain, but Hellraiser offers no reason for anyone to open the puzzle box. In no world is getting ripped apart by hooks even remotely pleasurable. The film doesn’t understand its core conceit. Frank calls his experience with the Cenobites “Pain and pleasure, indivisible,” yet we only see him in agony as he’s ripped apart and drenched in an amount of blood that makes Kill Bill look chaste.

Maybe, at one time, Clive Barker and Hellraiser seemed like a breath of fresh air. The 1980s were a strange time; Stephen King was in a fallow period, and Peter Straub hadn’t replicated King’s success. Horror is a big sandbox, and there’s room for all different kinds of takes on the genre. I’m not opposed whatsoever to a gory, disturbing film that examines sadism and masochism. This, however, is not that film. There are eleven films in the Hellraiser series. I can’t think of a good reason for there to be even one.

10/1: Hellraiser / The Invitation

10/2: Splice / Banshee Chapter

10/3: Jennifer’s Body / Raw

10/4: Dominion: Prequel to The Exorcist / Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2

10/5: Kill List / A Field in England

10/6: Halloween II / Halloween III: Season of the Witch

10/7: A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge / A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors

10/8: Ginger Snaps / Creep

10/9: Cube / Creep 2

10/10: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2003) / The Ritual

10/11: Hell House LLC / The Taking of Deborah Logan

10/12: Re-Animator / From Beyond

10/13: Beetlejuice / Sleepy Hollow

10/14: Idle Hands / The Lords of Salem

10/15: The Ring / Noroi: The Curse

10/16: I Know What You Did Last Summer / The Monster

10/17: Night of the Living Dead / Train to Busan

10/18: The Devil’s Backbone / Southbound

10/19: Event Horizon / Dreamcatcher

10/20: The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari / The Bad Seed

10/21: Eyes Without a Face / Goodnight Mommy

10/22: The Strangers / The Strangers: Prey at Night

10/23: In the Mouth of Madness / The Void

10/24: The Amityville Horror / Honeymoon

10/25: Gerald’s Game / Emelie

10/26: The Monster Squad / Behind the Mask: The Rise of Leslie Vernon

10/27: Veronica / Jacob’s Ladder

10/28: High Tension / You’re Next

10/29: The Innkeepers / Bug

10/30: The People Under the Stairs / Vampires

10/31: Saw / Saw II